Many people lament the fact that covid became political. It is often desired that there could have been a greater sense of solidarity among the public, and a broader public consensus on pandemic interventions. In the United States, for much of the pandemic, the stringency of virus-related restrictions correlated to which political party had jurisdiction. However, when considering the approach to the pandemic pushed by health agencies, and the manner of communication to the public, politicization was inevitable.

The purpose of this article is not to declare whether any particular mitigation measures taken by governments were right or wrong. Rather, it is to explain why public health officials communicated to political leaders and the general public in a way that represented a radical departure from the spirit of public health before 2020, and why politicization of science and health resulted.

Much insight can be gained from a 2006 paper titled “Disease Mitigation Measures in the Control

of Pandemic Influenza” (https://doi.org/10.1089/bsp.2006.4.366). The paper was written by four mainstream epidemiologists, all associated at the time with the Center for Biosecurity of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Baltimore, Maryland. Most notable perhaps was the author D.A. Henderson, who led the international program to eradicate smallpox in the 1960s and 70s.

This paper was written at a time when there was much concern that bird flu would mutate and gain the ability to spread easily between humans, leading to a pandemic. In the introductory section, the paper lists a variety of mitigation measures that had been proposed:

“Isolation of sick people in hospital or at home, use of antiviral medications, hand-washing and respiratory etiquette, large-scale or home quarantine of people believed to have been exposed, travel

restrictions, prohibition of social gatherings, school closures, maintaining personal distance, and the use of masks” (366).

These measures probably sound familiar. However, the paper describes the lack of clarity on the efficacy of such measures:

“However, there are few studies that shed light on the relative effectiveness of these measures. A historical review of communities in the U.S. during the 1918 influenza pandemic identified only two that escaped serious mortality and morbidity. Both communities had completely cut themselves off for months from the outside world. One was a remote town in the Colorado mountains, and the other was a naval training station on an island in San Francisco Bay” (366).

This is noteworthy especially considering that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the only countries that avoided serious mortality and morbidity were ones such as Australia, New Zealand, and some island microstates that shut themselves off from the world, starting very early in the pandemic and continuing until mass vaccination.

The paper proceeds to note that “other studies have suggested that, except in the most extreme applications, disease mitigation measures have not had a significant impact on altering the course of an influenza pandemic” (366).

During COVID-19, aforementioned countries such as Australia did succeed in stopping outbreaks within their own borders, but it took “extreme applications” of mitigation measures, and even these strategies failed when more transmissible variants arrived.

The paper goes to describe the inherent dilemma of pandemic mitigation measures:

“Many could result in significant disruption of the social functioning of communities and result in possibly serious economic problems. Such negative consequences might be worth chancing if there were compelling evidence or reason to believe they would seriously diminish the consequences or spread of a pandemic. However, few analyses have been produced that weigh the hoped-for efficacy of such measures against the potential impacts of large-scale or long-term implementation of these measures” (366-367).

This is a consideration that seemed to be missing in the COVID-19 response, namely, that major social and economic disruption is only justified if it significantly alters the trajectory of a pandemic. Instead, the mentality during COVID-19 was that intense disruption was justified if there was potential for, at best, a modest slowing of the spread.

Public health officials often tried to justify covid mitigations by saying that “covid is not like the flu,” citing pre-symptomatic and asymptomatic spread. However, this paper on pandemic influenza management is conscious of such risks:

“People infected with influenza may shed virus for 1–2 days before becoming symptomatic. Some flu-infected individuals may be asymptomatic and so would not be recognized as being infected. In seasonal flu outbreaks, this group may represent a significant proportion of infected people. Asymptomatic individuals infected with flu have been shown to shed virus” (367).

Contrary to what was often perceived during Covid, shedding virus in the pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic phase are not new phenomena that would warrant an overturning of conventional thinking on epidemiology.

The paper proceeds to discuss the disease burden expected during a pandemic:

“While government planners estimate that as much as 30% of the U.S. population would fall sick from the next pandemic, any given community would see those illnesses spaced over a period of at least 8 weeks, not all occurring at one time. Since the average duration of illness would be expected to be about 10 days, only a subset of flu victims in any community would be ill at once. Given this, even in the peak weeks of a pandemic it would seem reasonable to expect that no more than 10% of a community’s population would be ill at any time” (367).

The COVID-19 pandemic seems to have fallen within these assumptions. The paper predicts that up to 30% of the population would develop symptomatic illness. In the United States, the most significant covid waves took place between January 2020 – March 2022. During that period, there were 81,906,643 cumulative cases in the U.S. (https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/us/). This is about 25% of the country’s population.

The paper also predicts that less than 10% of a community’s population would be ill at a given time. This also appears to have been true during COVID-19. For example, consider South Dakota, a small state with no state-level restrictions on public activity from May 2020 onward. At the peak of the pre-vaccine wave in Fall 2020, there were 19,360 “active cases” in a population of 884,659 (https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/usa/south-dakota/). This equates to only 2% of the state’s population. Even if this were multiplied by up to 5x to account for unreported cases, it is still within the estimates for peak virus activity in the paper we are looking at.

The paper goes on to describe the lethality of pandemic viruses:

“In the worst case, the case-fatality ratio would be equal to that of 1918 (about 2.5%). Such data as are available from the past 300 years show the 1918 influenza pandemic was, by far, the most lethal” (367).

During the first COVID-19 wave for which there was mass testing throughout the whole United States, (September 2020 – March 2021), there was a case fatality rate of 1.5%, based on Worldometer’s data. This is on the more severe end of the historical spectrum of pandemics from flu-like disease. However, at the end of this article, I have a section on why I believe the severity of a pandemic is determined by the health of the population rather than the virus itself.

Now we will move on to the section of the paper which discusses pandemic mitigation in more detail. Regarding the different levels of government in the United States, the paper states:

“It has been recognized that most actions taken to counter pandemic influenza will have to be undertaken by local governments, given that the epidemic response capacity of the federal government is limited” (367).

Contrary to this, from the very start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the expectation among both the general public and medical professionals was that the federal government must lead the response. This contributed to the politicization of covid, given that the general public was sharply divided in how it perceived the Trump administration and later the Biden administration.

One mantra during COVID-19 was “flattening the curve.” The paper describes this concept:

“A fundamental premise of disease mitigation that has been advanced by some in the policymaking community is that a less intense but more prolonged pandemic may be easier for society to bear, but this is speculative” (368).

It certainly did not seem “speculative” during COVID-19. It was presented as an obligatory approach that could not really be questioned.

Regarding politicians, the paper states:

“Political leaders need to understand the likely benefits and the potential consequences of disease mitigation measures, including the possible loss of critical civic services and the possible loss of confidence in government to manage the crisis” (368).

Confidence in government is critical. For mandates to be successful, the public must be confident that the government has the public’s best interests in mind, and confident that the mitigation measures are actually accomplishing the intended goal. During COVID-19, there were neither. Many people felt oppressed by mandates, and despite profound disruption to the economy and social life, there were explosive rises in cases and constant media depictions of hospitals overwhelmed. People did not feel free nor safe.

Regarding hospitals, the paper states:

“Modern hospitals are not designed to accommodate large numbers of highly contagious patients, and special measures, including cohorting of patients, adjustments to HVAC systems, and use of personal protective gear, will need to be made to protect healthcare workers and patients from infection …

“Accommodating the increased demand for hospital care will require coordination and collaboration between hospitals in a given region and among hospital leaders, public health authorities, and elected officials …

“A major challenge for all authorities charged with managing a pandemic will be how to allot scarce, possibly life-saving medical resources and how to maintain hospitals’ capacity to care for critically ill flu victims while continuing to provide other essential medical services” (369-370).

The paper recognizes the critical importance of hospitals in a pandemic, but it also portrays it as the government’s responsibility to enable hospitals to carry out necessary medical care. Nowhere does the paper suggest that the public has a responsibility to change its behavior in order to save the hospital system. Yet the latter was preached incessantly during COVID-19, further inflaming the politicization because people blamed those they disagreed with for hospitals being stressed. The federal government spent trillions of dollars to support businesses and individuals financially during lockdowns. This was money that could have been given to states to ramp up their hospitals.

Regarding handwashing, the paper states:

“The influenza virus actually survives on the hands for less than 5 minutes, but regular hand-washing is a commonsense action that should be widely followed. It has been shown to reduce the transmission of respiratory illness in a military trainee setting, although there are no data to demonstrate that hand-washing deters the spread of influenza within a community” (370).

The paper acknowledges that it is not known whether hand washing reduces influenza spread in community settings, but it still recommends the practice. Hand washing does not cause major trouble for people, especially after the invention of hand sanitizer gels and sprays.

The paper continues:

“General respiratory hygiene, such as covering one’s mouth when coughing and using disposable paper tissues, is widely believed to be of some value in diminishing spread, even though there is no hard evidence that this is so” (371).

Covering your mouth when you cough is really just basic courtesy. Who wants to be coughed on? Yes, there’s a lack of “hard evidence” for efficacy, but we don’t need such evidence to recommend something that is simple manners.

Regarding home quarantine:

“Voluntary home quarantine would be requested of individuals who are asymptomatic but who have had substantial contact with a person who has influenza—primarily household members. The aim of voluntary home quarantine is to keep possibly contagious, but still asymptomatic, people out of circulation. This sounds logical, but this measure raises significant practical and ethical issues ...

“How compliant the public might be is uncertain. Parents would presumably be willing to stay home and care for sick children, but it is not known, for example, whether college students would agree to be interned with infected dorm-mates ...

“For those who are hourly workers or who are self-employed, the potential loss of wages as a result of having to stay home simply because an individual had had contact with sick people might not be acceptable or feasible …

“A policy imposing home quarantine would preclude, for example, sending healthy children to stay with relatives when a family member becomes ill” (371).

The first thing I want to note here, is that this paper is questioning whether it is practical and ethical to quarantine people who have “substantial contact” with known influenza cases. Contrast that to the COVID-19 pandemic, when people were sometimes expected to quarantine at home if they had merely been among a group of people who were not masking and distancing. Later on in the paper, the authors warned again of “loss in public trust in government” as a consequence of quarantine (p. 373), and this is with much more targeted quarantines than what was attempted during COVID-19.

One problem with quarantine cited by the paper is that it could prevent “sending healthy children to stay with relatives when a family member becomes ill.” But during the COVID-19 “shelter-in-place” orders, family members of different households were forbidden to visit each other, even if nobody in either household had any symptoms of illness or known exposures to covid.

Regarding prohibition of social gatherings:

“There are many social gatherings that involve close contacts among people, and this prohibition might include church services, athletic events, perhaps all meetings of more than 100 people. It might mean closing theaters, restaurants, malls, large stores, and bars. Implementing such measures would have seriously disruptive consequences for a community if extended through the 8-week period of an epidemic in a municipal area, let alone if it were to be extended through the nation’s experience with a pandemic (perhaps 8 months). In the event of a pandemic, attendance at public events or social gatherings could well decrease because people were fearful of becoming infected, and some events might be cancelled because of local concerns. But a policy calling for communitywide cancellation of public events seems inadvisable” (372).

The paper recognizes that such prohibitions would be “seriously disruptive” even if enacted for just an 8-week period. During COVID-19, in many jurisdictions these measures were enacted in varying degrees for 14 months. Without making a judgment on the merit or necessity of such restrictions, I believe it is safe to say that such restrictions had a heavy social and economic impact which further damaged public confidence in governments’ management of the pandemic and contributed to the politicization of covid.

Regarding social distancing:

“It has been recommended that individuals maintain a distance of 3 feet or more during a pandemic so as to diminish the number of contacts with people who may be infected. The efficacy of this measure is unknown. It is typically assumed that transmission of droplet-spread diseases, such as influenza, is limited to “close contacts”— that is, being within 3–6 feet of an infected person” (372).

Three-foot distance is not a lot more than the “personal space” that is customary in American culture. But during COVID-19, public health guidance was adamant that the distance be six-foot, even though, as this paper noted, the efficacy of physical distancing was unknown. Perhaps, three-foot distancing could have fallen into the category of mitigations practical enough to accept unknown efficacy, but six-foot distancing made normal life very problematic, and one could have reasonably expected more evidence.

Regarding community masking:

“Studies have shown that the ordinary surgical mask does little to prevent inhalation of small droplets bearing influenza virus. The pores in the mask become blocked by moisture from breathing, and the air stream simply diverts around the mask. There are few data available to support the efficacy of N95 or surgical masks outside a healthcare setting. N95 masks need to be fit-tested to be efficacious and are uncomfortable to wear for more than an hour or two. More important, the supplies of such masks are too limited to even ensure that hospitals will have necessary reserves” (372).

To my knowledge, the best result for community masking that we ever got from a controlled study during COVID-19 was the Bangladeshi mask study, which showed only an 11.1% reduction in symptomatic seroprevalence among the groups who wore surgical masks (Impact of community masking on COVID-19: A cluster-randomized trial in Bangladesh – PMC (nih.gov)). But in the United States, the mask became the ultimate symbol of whether people took covid seriously, were scientifically knowledgeable, and cared about other people. But the quote above on community masking from the 2006 paper is enough reason to say that the mask should have never become such a symbol.

During the second winter of the pandemic, N95 and similar respirator masks became available to the general public. Theoretically, these masks would address the issues that limited the efficacy of cloth and surgical masks. But they have to be worn tightly to have this effect, which is rather uncomfortable, and many people I saw wearing them in public wore them loosely such that they would not be effective against airborne particles.

Regarding vaccination, the paper states:

“Vaccines are the best mechanism for preventing influenza infection and spread in the community and for

protecting healthcare workers caring for those who do become ill. Once an influenza strain capable of sustained human-to-human transmission emerges, a vaccine specific to the pandemic strain will need to be made. It is expected that it will be at least 6 months after the emergence of the pandemic strain before the initial supplies of vaccine can be produced” (369).

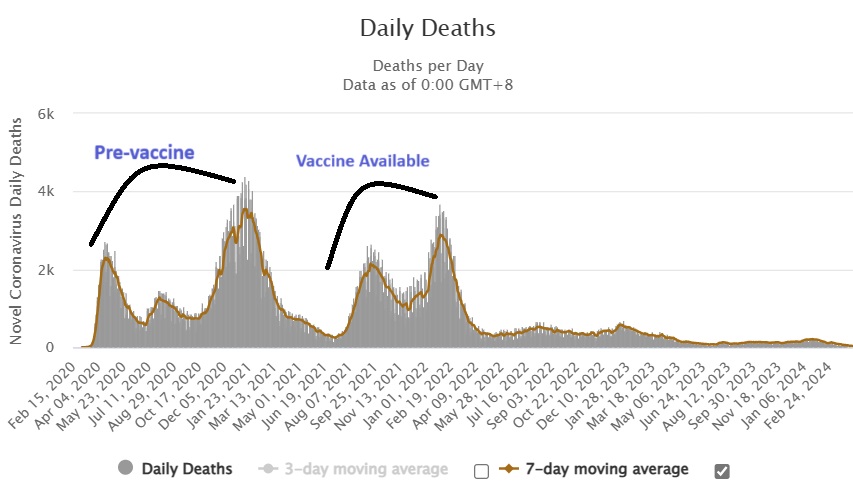

Due to the time it takes to develop a new vaccine, the first fall-winter season of a pandemic is likely to come and go before a vaccine is available to most people. However, vaccination can be helpful in reducing the severity of subsequent waves. During the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccination reduced the case-fatality rate by an order of magnitude.

In Australia, the vast majority of covid cases occurred between December 2021 and January 2023, during which time there was high vaccine coverage. During that period, the case fatality rate was 0.1%, comparable to seasonal flu. In the period prior to December 2021 (which was mostly pre-vaccine in Australia), their case fatality rate was 1.0% (https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/australia/).

In the United States, vaccine uptake was low in some regions of the country, and consequently, the U.S. had two additional severe waves of covid beyond the first winter.

Source: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/us/#graph-deaths-daily

People should decide for themselves whether or not to get vaccinated. In the case of COVID-19, given the health issues in many industrialized countries (discussed more later), the populations as a whole appear to have benefitted from covid vaccination. In my article here, I show graphs of excess mortality trends from the website EuroMOMO. In Western European countries (which generally had high vaccination rates), there were no major waves of covid mortality after mass vaccination in mid-2021. At a personal level, on the other hand, individuals may have their immune health in better shape than the general population; in which case, I cannot say whether or not they should get vaccinated based on macro-level data.

With regards to mRNA vaccination, I am reminded of the old saying, “when there’s smoke, there’s fire.” But in this case, the smoke (anecdotal evidence of an usually high rate of vaccine injury, including testimonies from doctors) is thick and rampant, but the fire (high quality, population-level evidence of widespread vaccine injury) has been elusive. All I can say is that people should have felt free to exercise their own judgment.

Below is the conclusion of the 2006 paper we have been looking at on pandemic management:

“Experience has shown that communities faced with epidemics or other adverse events respond best and with the least anxiety when the normal social functioning of the community is least disrupted.

Strong political and public health leadership to provide reassurance and to ensure that needed medical

care services are provided are critical elements. If either is seen to be less than optimal, a manageable epidemic could move toward catastrophe” (373).

So, then, what should we say? It is hard to imagine more anxiety and disruption than what many people experienced during the pandemic response. What we can say, on the basis of this paper, is that the social restrictions introduced during COVID-19 were not common-sense measures rooted in epidemiological science. Rather, they were highly experimental measures. I cannot prove to you that these measures were the wrong approach (just as I cannot prove that they would be wrong during seasonal flu epidemics). These are public policy questions that cannot be answered with hard science alone. But nevertheless, there was no basis to assert that because we were in a pandemic, these were the things we had to do.

My biggest concern about what happened during covid involved something deeper than government mandates. It was the social harm in which people shamed and ostracized people who did not “follow all the precautions.” Friendships ended and family relations were strained over this. On one hand, I am a believer in following rules set by the authorities even if they are not rooted in sound science. I never advocate civil disobedience. But my chief concern was that, apart from government regulations, people were essentially policing each other.

The reason people did this is that they believed they were helpless against COVID-19 in the absence of a vaccine and antiviral drugs (and everybody around them also being vaccinated). But this fear stems from a faulty narrative about pandemics, which is that certain influenza viruses or coronaviruses are extremely deadly. The term “once-in-a-century virus” was used to describe covid. But are there really monster influenzas or coronaviruses that spring up once in a while? Or are the unusually severe pandemics caused by something other than the viruses themselves? And are there things people can do for their immune health in order to avoid facing an exceptional risk from new viruses?

The 1918 pandemic, which had a 2.5% case fatality rate, is often cited to illustrate the danger of new viruses. But was there really a new influenza virus with unique properties that made it more deadly than any other flu pandemic in history? Or was the health of the population compromised circa 1918, making people more susceptible to severe outcomes from infection with a new virus?

In the book Virus Mania, the authors (among them Dr. Claus Köhnlein, a practicing physician with experience treating patients with infectious diseases) make the case that major non-viral factors were at play during the severe morality waves of that era:

–“Psychological stress, evoked by fears of war.”

-“Over-treatment with chemical preparations, which can seriously compromise the immune system, including painkillers like Aspirin and chloroform. Chloroform was used as a preservative in medications and is metabolized in the liver into phosgene, an agent used as a poison gas in the First World War. In the late 19th century, manufacturers of medicinal products also increasingly began selling products that contained highly toxic substances like morphine, codeine, quinine, and strychnine as medicines; as at that time there were no regulations for such manufacturers.”

-“Damage to airway organs resulting from ‘preventative’ measures, like rubbing the throat with antiseptic preparations or inhaling antibacterial substances. Many of the substances used at that time also contained the toxic metal silver and have since been prohibited (for example, Formalin/formaldehyde has strong corrosive and irritating effects on the skin, eyes, and airway…).”

-“No effective antibiotics: many people were afflicted by bacterial and fungal infections; however, the first really effective means of killing bacteria and fungi was penicillin, which was discovered much later, in 1928.”

-“Vaccines often contained toxic heavy metals and were produced out of poorly filtered mucus or other fluids from infected patients.”

Source: Engelbrecht, Torsten, et al. Virus Mania. 3rd English Edition, 2021. Pages 252-254. Kindle Edition

It seems probable that by the time people in 1918 got really sick, they were suffering from bacterial superinfections rather than active viral infections. Although, almost eighty years later, anatomical remains of several people who died in 1918 were found to have RNA fragments from an Influenza A/H1N1 virus, experiments conducted during 1918, which were aimed at transmitting the disease from sick people to healthy people, consistently failed. The documentation of these experiments can be found in the CDC’s database of historical public health reports (https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/67902).

The subsequent influenza pandemics of the 20th century (1957-58, 1968-70, 1977-79) were not much worse than normal influenza outbreaks. Pharmaceutical regulations had made drugs and vaccines safer, living standards had improved through the post-WW2 economic boom, and unlike 1918, there were antibiotics to treat bacterial superinfections.

COVID-19 was caused by a novel coronavirus, occurring in an era where diet and lifestyle issues in many industrialized countries have led to poor metabolic health, with a consequence being vitamin D deficiency. Without adequate vitamin D, the immune system is prone to launching an inflammatory interleukin storm when fighting a novel virus, which can lead to acute respiratory distress. A 2021 study showed that mortality from COVID-19 could be theoretically near-zero with ideal vitamin D serum concentrations (https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8541492/).

In addition to vitamin D supplementation, for people who are worried about viral illness, here are recommendations from the book Virus Mania for how to keep the immune system in good shape to encounter viruses:

-“Ensure a diet rich in fiber, bases and vital substances with many active enzymes, vitamins, minerals and trace elements-and if possible without toxins (pesticides).”

-“Eliminate or reduce processed and nutrient-poor ‘foods’ such as refined sugar from your diet. They are robbers of vital substances and burden your immune system.”

-“Try as much as possible to avoid negative stress and at the same time strive for fulfilling experiences. Exercise or sport is essential for this balance.”

-“Measures providing extra support for the immune system include glutathione administration or intravenously administered nutrient and base infusions if indicated.”

-“High-dose vitamin C administration can also be highly beneficial during health crisis.”

Source: Engelbrecht, Torsten, et al. Virus Mania. 3rd English Edition, 2021. Page 306. Kindle Edition

In my blog article titled “The Early Treatment Quandary and the Harm Caused by Censorship,” I discuss the vastly different excess mortality rates from country to country during 2020-21. This is further evidence that the health of a population, rather than the virus itself, determines the severity of a pandemic. Some countries had no significant excess mortality throughout the entire pandemic period.

Covid became political because, instead of focusing resources on empowering the population to reduce their risk of severe disease, and gearing up hospitals to treat people who did become seriously ill, pandemic mitigation revolved around controlling the social behavior of the population. And control over the population’s behavior is the very definition of politics. In the U.S., trillions of dollars from the government went into social distancing endeavors. It is rather ironic that the most politicized pandemic in history was caused by a coronavirus (corona means “crown”).

In the end, it was immunity that won the battle for power. Despite media alarm bells ringing and certain voices on social media screaming every time a new subvariant of covid emerges, waves of covid morbidity and mortality since mid-2022 have been subdued by immunity in the population, both in the U.S. and around the world, and people are living normally. Whenever the next pandemic happens, it would be great for immune health to have a stronger voice in pandemic discourse from the beginning.